A father’s story of suicide loss

In the spring of 2009, my daughter phoned and asked if she could ‘pop by’ for a few days. I was pleasantly surprised because it sounded like she was just around the corner. In reality, she was still 600 km away, dropping off her boyfriend for his seasonal job in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. It was work that they had formerly shared–packing supplies into a remote wilderness reserve with horses and mules, 3000 metres or more above sea level.

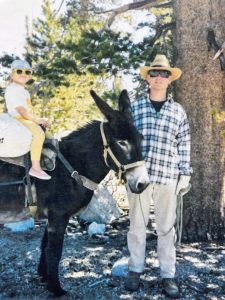

Amy first rode into those mountains on a donkey when she was four. At 13, she began to work summers there, loading and leading strings of donkeys into the backcountry. Because she had grown up in the Mojave Desert, the trees and meadows of the Sierras always seemed spectacular to her.

However, by 2008 Amy was 22 and wouldn’t be working with pack animals again. She had taken a one-year leave from her Neuroscience PhD studies in Arizona to visit fellow equestrians in Montana. Sadly, this is where she suffered a freak accident and broke her back. Her spinal cord was not damaged but she spent five months in a full-torso cast. After that was removed, she was able to walk normally but the surgeons said she could not ride horses again nor lift anything heavier than five kilos.

Amy seemed to be adjusting to these new restrictions and rejoined her academic life in early 2009. Still, it must have been difficult to drop off her boyfriend in the Sierras and then return to Arizona alone. I suspect that’s why she called me about coming for a visit. Not only did Amy and I have a fun-filled week together in Northern California, we took an 800 km road trip south to visit her aunt and grandparents near Los Angeles. After that, we all said our good-byes and Amy drove back to Arizona. Little did her family and friends know, this was her farewell tour.

Two days later, I got a call from Amy’s mother. She and I had been divorced for a decade at that point, so I couldn’t figure out why she would be calling me early on a Sunday morning. Apparently, she had not been able to reach Amy and wondered when I had last seen her. I told her not to worry, Amy was sad about not being able to work in the mountains but was doing well and was probably sleeping after the long drive or, maybe she missed her boyfriend and drove up to see him in the mountains.

As it happened, Amy did go back to Arizona. The next day, my local police called and said that an officer and a chaplain were on their way to my ex-wife’s apartment. That’s when life began to feel like an out-of-body experience. The two of them told us that Amy had died and they provided the phone number of a Pima County Sheriff’s detective to call for more information. He confirmed that Amy was dead and was then overcome with emotions that had not yet hit me, because I was in shock. Amy and I had just been together. How could she be dead?

The detective recovered his composure and patiently went through why he believed it was suicide. I questioned his reasoning but, in the end, it made sense. Part of what convinced me was reading the copies he shared of letters that Amy had left behind for her mother, me, and her boyfriend. Basically, she wrote that she’d been depressed for the past few years but didn’t want to worry us because she had been able to cope by recharging her spirit in the mountains every summer. Now, with that annual mood boost no longer possible, she couldn’t bear living. What? That’s from the same seemingly-joyful daughter I had just spent time with?!?

I returned to my apartment and (for three days) just sat in a chair cursing in four-letter words. How did I miss the signs? Were there clues or should Amy get a Best Actress award? Soon enough I had to pull myself together and arrange to pick up her boyfriend in the mountains, so that we could go to Arizona.

Amy’s boyfriend and I helped each other through that first week of legal details and clearing out their apartment. We had to do everything together because neither of us could make it through a full conversation on the phone or any public interaction without breaking into tears. When one of us began crying, the other would pick up the conversation, until they too broke down.

A month later, we had a memorial, and people came from across the country to share their grief. It was great to feel their love and support, but then what? I met with a therapist but that didn’t really help. I also tried a group for parents whose child had died, but did not feel welcome or understood. Then I found a group led by a couple who had lived through the experience of losing their son to suicide. Ah, these were my people! The group felt comfortable and comforting.

By 2014, I had recovered enough to travel for pleasure again. I decided to indulge my interest in open-water swimming and joined a Swim Trek holiday in the Mediterranean. There, I met an interesting Irish woman, Susan, from London, and we connected on so many levels. Long story short, we were married two years later and settled in Spain. In early 2024, we moved to Ireland. Being back in an English-speaking country gave me the opportunity to seek out a peer-led group for those bereaved by suicide — and that’s how I found HUGG. I attended meetings in Waterford for several months before volunteering to help launch a new HUGG group in Wexford. The idea of post-traumatic growth gives me hope (growing around your grief), and I deeply believe in the value of postvention — offering support to those left behind after a suicide, to help reduce risk and create space for healing.

I credit Susan for helping me discover how much I had grown through my grief. She believes it’s courage, but I think it was hope that allowed me to regain my life and venture falling in love again.

My best wishes to you, on your own journey,

Dirk, June 2025